The case for product passports

Product categorisation standards already exist and they fundamentally support the trade and sale of services and goods around the world. They are also a relatively recent development — for example, the first product to display a barcode was a pack of chewing gums in 1974. Now try running a supermarket or a fashion store without barcodes.

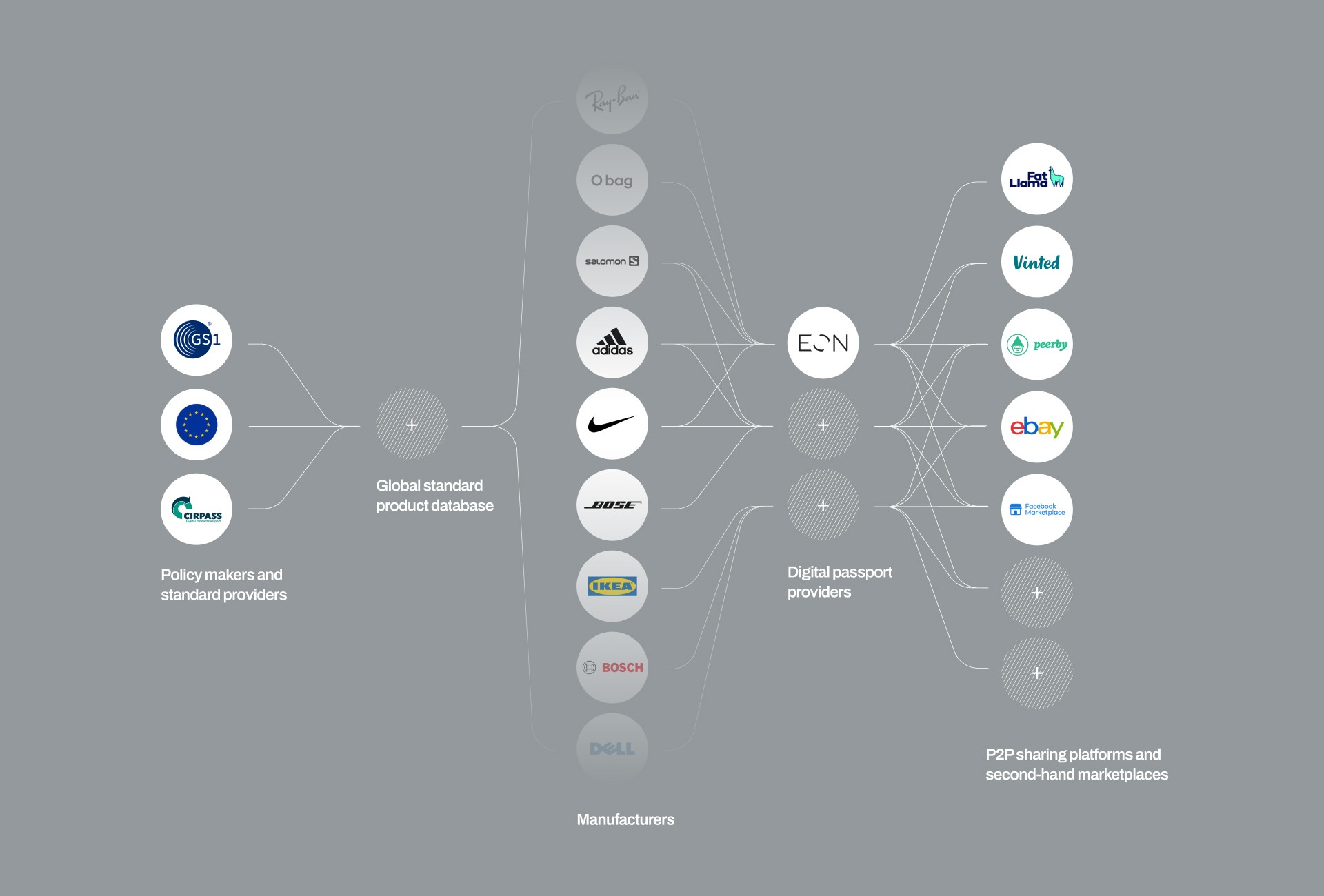

We envision an extension of product standards — for example, the Global Trade Item Number (GTIN), currently managed by the non-for-profit GS1 — to allow the storage of additional product information. Product description, materials, nutritional information, images, and recommended price, could all be added to this extended product passport. Product owners could then link this data to their e-commerce platforms or product management systems.

Ideally, the responsibility for the creation of a product passport standard would lay in the hands of public or not-for-profit organisations (like GS1) to guarantee a global standard and avoid the creation of too many data lakes.

One step further: unique product passports

GTIN and other product standards usually identify a product, but not the unique object. Although potentially expensive — potential economies of scale should be evaluated —, assigning a unique code to each individual item would unlock considerable new opportunities.

On the producer’s side, a unique product code would improve traceability and analytics, it would guarantee product authenticity, and it would remove the need for additional serial numbers (think of electronics).

Producers could also add dynamic branded content, allowing a more direct connection with the customers through the product — imagine to be able to play how-to videos by scanning the GTIN on your drill, or to be able to purchase expansions for your board game.

Consumers could gain considerable benefits too. Sharing and reselling, the core starting point for this analysis, would become way faster and easier: imagine simply scanning a product with your phone, and mark it for sale on multiple P2P platforms, with just one click.

Have you lost your glasses, wallet, coat, or earplugs? People who found theme could simply scan the tag with their phones, and reach out to you. Products would also be harder to steal, as each product could be uniquely marked with a physical person.

Or again: imagine to quickly contact customer support (and the agent knows already the specific product it is being inquired about).

Organic growth of sharing and reselling options

Although P2P product sharing platforms have mostly failed, we believe that the systematic introduction of product passports — especially in their second form described above, the one where each item receives a unique identifier — could make the difference in reaching that critical mass required for the proper success of sharing platforms.

A particular boost to second-hand sales would come from the unification of first- and second-hand platforms. As mentioned before, Amazon is a great example for this: used products are offered contextually with new products. While not common on other platforms, we could imagine proprietary e-commerce website and wholesalers introduce second-hand solutions, by connecting to the pool of products currently put for sale by private users.

While there are obvious advantages behind private ownership — for both economic systems and individual consumers —, a number of trends are putting the ownership paradigm under pressure.

Facilitating pick-ups and returns: street lockers

While product passports ease the burden of filling in the product information on sharing platforms, there is still one major burden to be addressed: pick-ups and returns. Renting out your drill or sleeping bag for a weekend means you need to agree with the borrower on a pick-up time on Saturday morning and a return time on Sunday evening. Far from ideal.

A similar business, home deliveries, has been faced for years with the same dilemma: how to deliver parcels to customers safely and conveniently, avoiding expensive missed deliveries? A range of solutions have emerged over time: emails with estimates of delivery time, delivery to neighbour, delivery to nearby stores or post offices, and delivery in street lockers.

In the specific case of product sharing, we argue that a growing number of street lockers could be one of the most convenient solutions to address the problem of pick-ups and returns. Not only they would serve as pick-up and return points for shared products, but they would also act as an extension of storage space, particularly useful for those living in tiny homes in dense urban contexts. Also, they can be easily located — e.g. they could be marked on Google Maps — in contrast to finding your way inside a large apartment building.