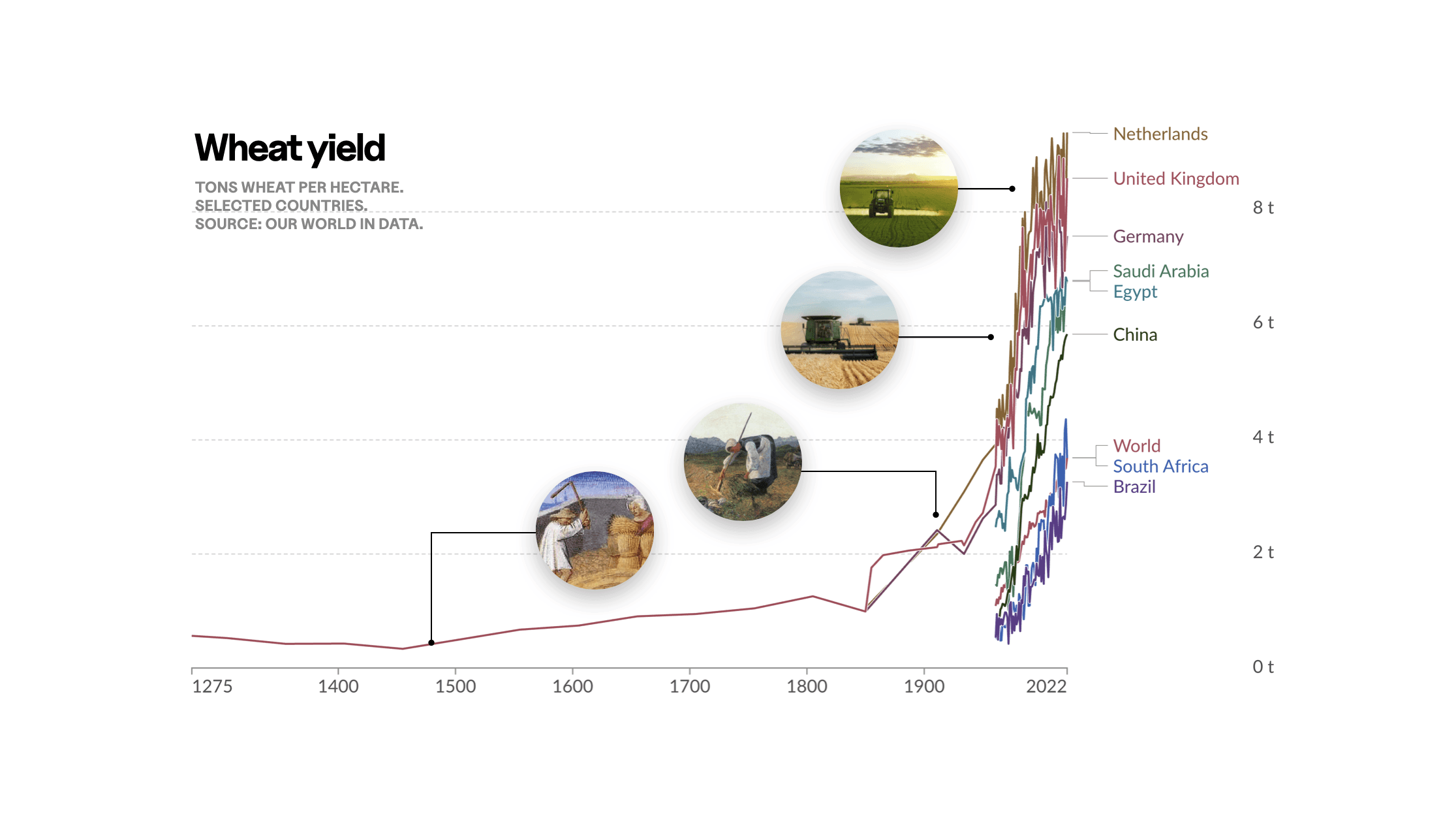

Nonetheless, new societal and environmental challenges and technological advancements are adding pressure on existing paradigms.

In this context, which transformations can we envision in the farming industry? Which architectonical futures can we imagine at the interplay of sustainability goals, emerging farming technologies, and ever-changing human needs and desires?

To answer these questions, one could simply redesign farms and greenhouses with only the interests of farmers in mind. This approach, although simple and linear, would fall short in future-proofing agricultural infrastructures.

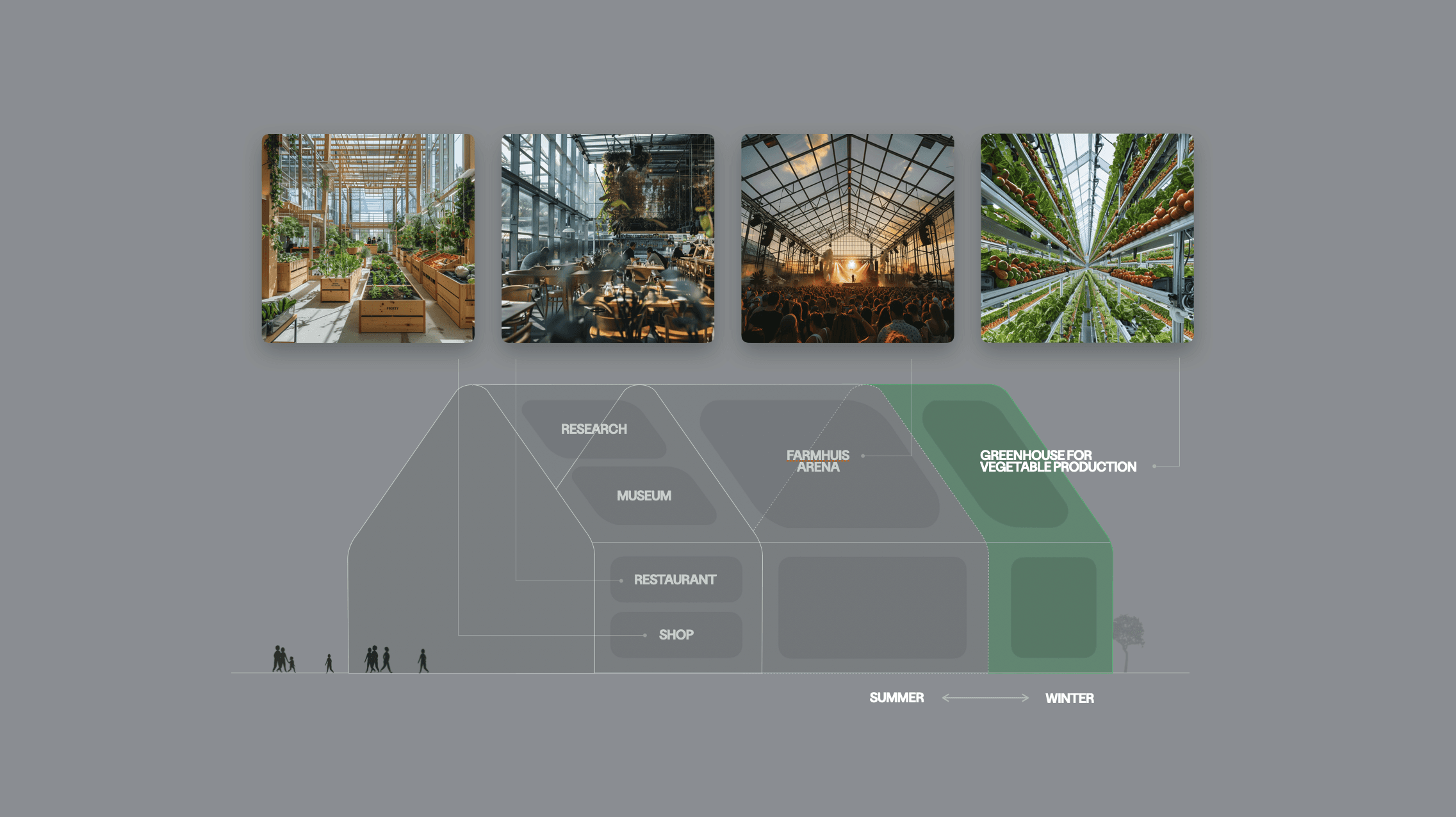

A wiser, future-savvy approach requires us to think of farming as part of the many systems on which it directly or indirectly has an impact. A complex, systemic approach that has the potential to unlock unprecedented synergies across industries and institutional interests.

Under this lens, we will have to invent farming solutions that are more resilient to the weather (1), from indoor farming (2) to the use of resistant crops.

We will have to bring farming closer to consumption, to lower transport emissions, and increase food freshness (6) and shelf life (5). Redistributed production paradigms could be of help here (8).

With an expanding and wealthier population, we will have to increase once again agricultural yields per unit of land - through vertical farming (2), high-precision agriculture (3), faster-growing cycles, and high-yield crops.

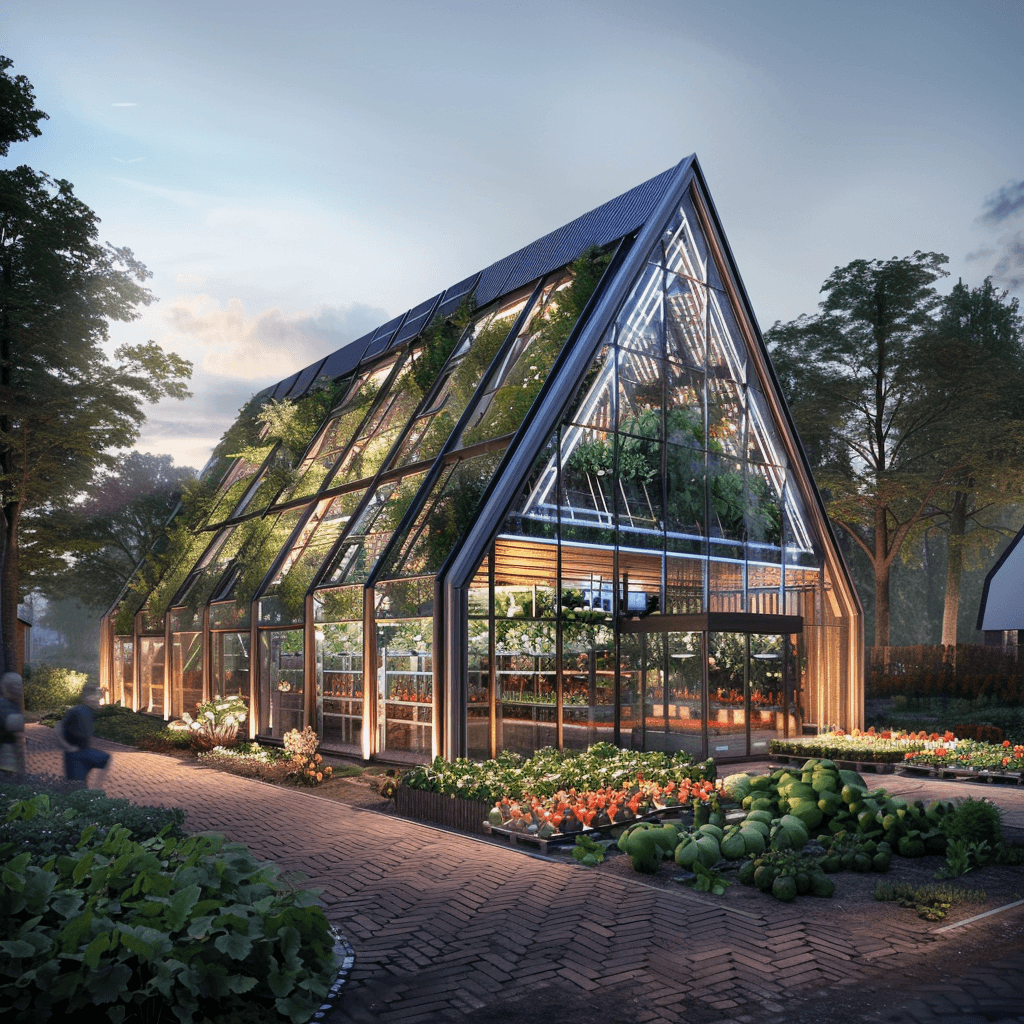

In turn, denser high-yield agriculture could bring greenhouses closer to city centres, with the potential for mixed-used infrastructures (7) through adaptable architecture, further reducing land use (4).

Finally, while innovating, respect could be paid to the historical traditions and architectonical solutions of the past (9).

At the crossroads of these individual transformations, entirely new farming paradigms could emerge — potentially transforming our urbanities and lifestyles just as much as the Industrial Revolution did.

Once we see farming as part of this complex web of interconnected interests, we have the unique opportunity to redesign agriculture (and the built environment around it) with holistic reach.

Once we see farming as part of this complex web of interconnected interests, we have the unique opportunity to redesign agriculture (and the built environment around it) with holistic reach.

For example, in contrast to the current centralised farming paradigm, with vast greenhouse establishments concentrated in a few production hubs across Europe, we could envision a decentralised network of smaller production centres.

Greenhouses, turned highly-efficient vertical farms, could make a comeback into villages and cities, bridging romantic pasts of traditional organic farming and modern technological high-yield production.

In a world where over 800 million people still are undernourished or stunted, new farming paradigms could become a scalable model for the poorest communities to guarantee food production, especially considering evolving climatic conditions.

Through alignment across large farmers, technology providers, research centres, grocery firms, and logistic solutions, we have the opportunity to rethink the future of farming, building new paradigms that provide more high-quality food, reduce waste, minimise externalities, while celebrating the past and promoting healthy nutrition.