We could imagine organisations — either public or private — as guarded castles: they have a coherent brand, a workforce, a headquarter, a portfolio of products and services, a set of values, and a long-term vision. A great majority of the time, their employees sit at their desks inside their "corporate castles", look inward, talk among themselves, and innovate internally.

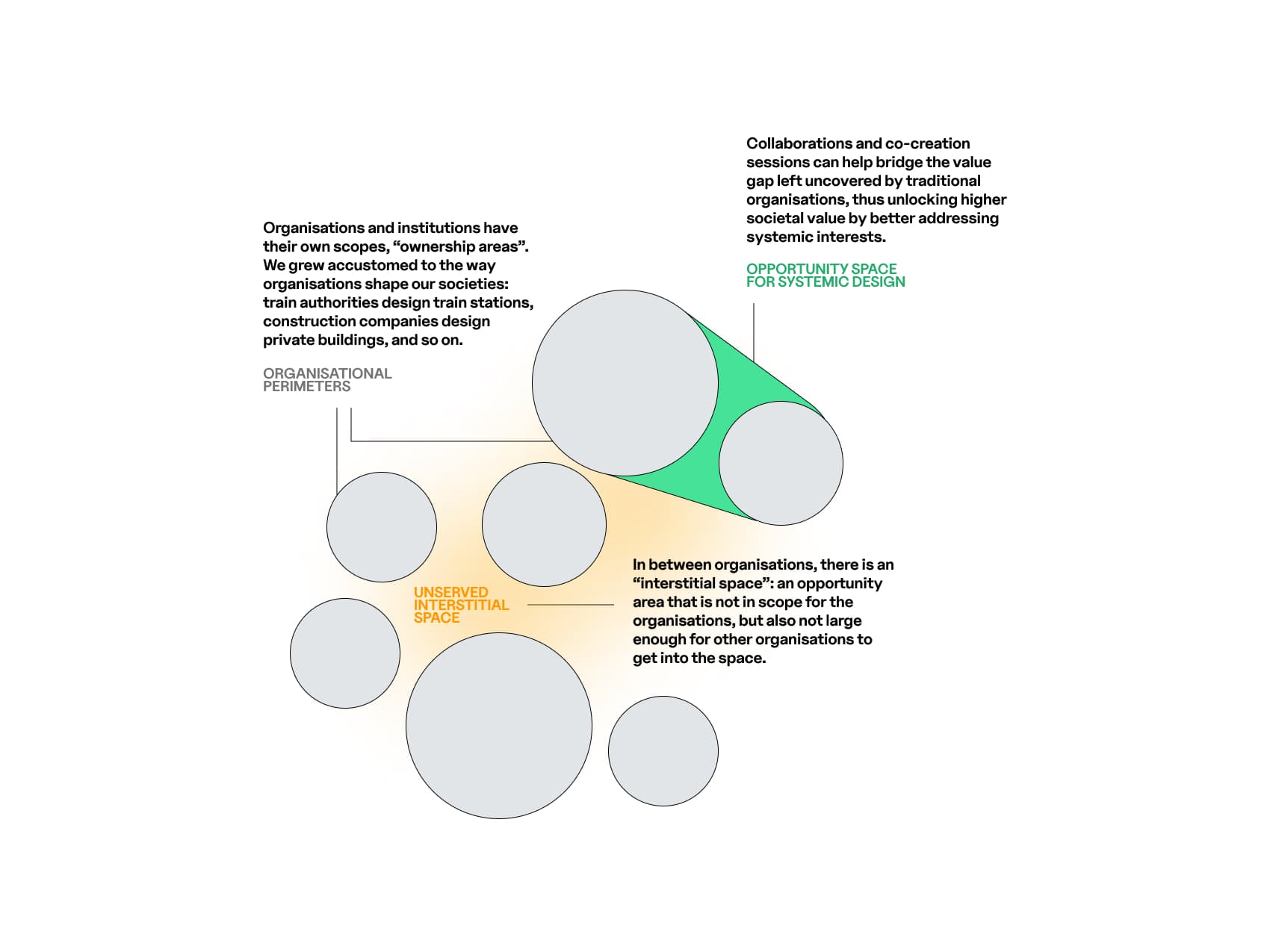

While each of these "castles" burst with life, activities, and ideas, much less happens between multiple castles, in an "interstitial space" that remains largely unserved. Multi-company innovation is rare, and when it happens, it is afflicted by complicated bureaucracy and diffidence.

And yet, behind these coordination barriers, we believe an entire class of innovation is hiding in plain sight: Systemic Design. A type of design and innovation that cannot happen inside one single castle — either because unviable from a business model standpoint, or unfeasible, because too complex. Design that requires a multi-stakeholder approach, not just at the operational level, but deeply embedded into the planning process. Design that brings about higher value for customers and citizens, often at a competitive price tag, thanks to complex, visionary, collaborative innovation.

Some examples may help to clarify what is achievable when different castles open their doors to mutual delegations — aka when different organisational interests meet in the same room, and design integrated solutions.

The first example comes from the Netherlands, where the Dutch rail company not only operates trains, but also, unconventionally, 21.500 smart bikes and an astonishing 5 million bike rides a year. These are the results of the "OV Fiets" program, which allows train riders to rent a bike from any of the over 400 train stations in the Netherlands, with just a tap of the national train card. As innocent as this may sound, this program had to require a train company to leave its own "castle", its own area of competence, and get a budget approved to buy bikes instead of trains, to build bike facilities deeply embedded in prime locations within their train stations, and to update the signage inside their train stations.

In a similar category fall the "artistic stations" in Stockholm' and Napoli's metro networks — like Toledo station in Napoli, or T-Centralen and Rådhuset Stations in Stockholm. These stations are not just cosmetically adding art into their spaces, but they literally are art themselves, becoming national monuments while serving as infrastructures as well. While many countries around the world have policies for embedding art into public infrastructures — like the Percent-for-Art Programs in the USA and Canada or the Kunst am Bau in Germany —, they rarely embed the artistic endeavour so deeply into the planning and design phase of the public infrastructure.

Another example of system design and collaborative innovation comes from Bergen, Sweden. Here the Fyllingsdalstunnelen, a 3km-long pedestrian and biking tunnel, the longest in the world, has opened in April 2023. A tunnel with a twist: the bike tunnel doubles as an escape route for the adjacent light rail tunnel. The county major Jon Askeland clearly showcases the project: "In order to get approval for the light rail tunnel, it had to have an escape tunnel. (…) The cool thing is that we are utilising necessary infrastructure, such as an escape tunnel, to create new connections and shortcuts between neighbourhoods". At a fraction of the cost of a dedicated tunnel, the city could solve two infrastructural needs with only one infrastructure.

Back to Amsterdam, meet the Sluishuis, an iconic residential building designed by BIG, an architecture firm, audaciously protruding towards the water and with a panoramic terrace on its rooftop. While most rooftop terraces in apartment blocks are private spaces, this one marks an exception, being required by the city of Amsterdam to remain open to the public for at least 80 days a year.

While these examples show a virtuous trajectory, they also show the rarity of this type of endeavours. In a way, they represent an entire new type of innovation practice — say, “Collaborative Innovation” — that, at the cost of higher degrees of alignment and trust, can generate superior design paradigms, and unlock larger pockets of societal benefit.

One more story, again from the Netherlands: the explosive growth of ASML, a renowned company that produces world-class machinery for the production of advanced semiconductors. The organisation is less an organisation than it is an ecosystem of partnerships: ASML outsources over 90% of what it costs to build one machine (up from roughly 60% of Boeing or 50% for Apple), and it directly employs less than half of the 100.000 people that directly or indirectly contribute to the design and construction of ASML machines — with the other half working instead in one of the 800 suppliers of ASML, which produce highly sophisticated components, often specifically designed with and for ASML.

While they may sound disparate, these stories have something in common. They are examples of successful innovation generated across typical business units, individual organisations, or budgetary constraints. They are examples of innovation that just cannot be performed by one single organisation or business unit.

While these examples show a virtuous trajectory, they also show the rarity of this type of endeavours. In a way, they represent an entire new type of innovation practice — Systemic Design — that, at the cost of higher degrees of alignment and trust, can generate superior design paradigms, and unlock larger pockets of societal benefit. It is a type of innovation practice that is hiding in plain sight, partially mimetised in the societal habit of thinking in terms of individual organisations and individualistic business behaviors.

Back to reality, as innovation practitioners, we are usually employed and paid by a single organisation, with selfish goals. In this context, where governance and incentive models typically shape most of innovation as an internal endeavour, how to get your organisation to unlock more Systemic Design?

Dynamic governance.

For the Dutch railways company to be able to finance a bike-sharing scheme, bike sharing had to be included into the sphere of influence of the railways company. Where the opportunity for cooperation or product integration exists, organisations and public administrations need to be able to plastically reshape, and ask for a mandate to innovate in adjacent fields on which they did not previously have a mandate on.Visionary thinking.

The combined know-how and assets of 2 (or more) organisations, working together on an innovation challenge, unlock unprecedented possibilities. Teams working on broad, systemic projects need to get used to, and leverage, the opportunity for visionary, unseen, transformative solutions, and become accustomed to communicating them to their management with enthusiasm. Systemic projects need to be much, not just marginally, better than single-company endeavours.Cooperative budget.

New dynamic and collaborative budget solutions need to be developed and contractualised, to make it easier for different organisations to jump on challenges together and allocate budget and resources to do so. These budgets should also remain dynamic throughout the process, to allow companies to get out of collaborative innovation tracks, when they see no more fit for them to be in the room — for example, your organisation could join (and pay for) an early exploratory phase of systemic innovation, and decide to step out if the strategic direction does not require anymore your involvement.Early embed.

The examples above all share systemic mindset early on in the design and planning process. Multi-stakeholder collaboration, in these examples, is not cosmetic and superficial. ASML does not just purchase components from many companies: it designs them together. The Sluishuis did not accidentally have a rooftop terrace — it was requested by the City of Amsterdam before the building was even conceived. The bike tunnel in Bergen was not a retrofit, but an original feature of the emergency tunnel. The underground stations in Napoli and Stockholm did not just install some artworks in their corridors: they included the artists (and the art & culture offices) straight from the planning phase.Systemic trust.

The financial costs and benefits of collaborative endeavours may be hard to split between organisations that work together, but it should not be a source of contempt, especially if the positive-sum effect of their collaboration dwarfs the costs and accurate splits. A certain degree of trust between organisations would help lubricate business relationships, making sure that the broader benefits do not get overhauled by mutual suspiciousness.

In conclusion, as an innovator within an institution, public or private, go beyond the organisational borders. Identify the broader systems you act in, and activate innovation in the interstitial spaces in between. Create imaginative narratives to inspire bold action, and envision budgeting mechanisms to allow for collaborative design across different organisations.